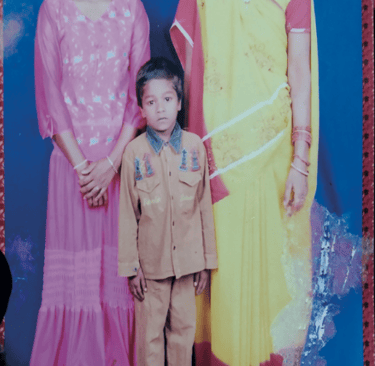

Anyone's Mother

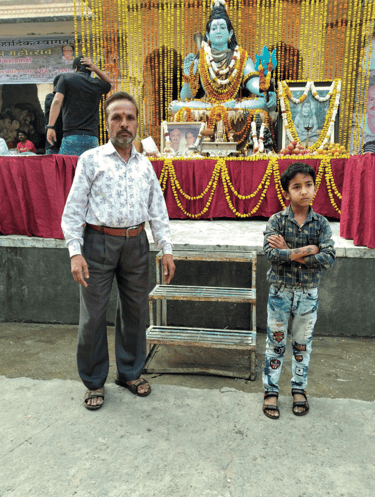

Anyone’s Mother is an archival work: within it converge—and intertwine into an unprecedented mosaic—images retrieved from the immense database provided by Google Maps. Indian women and men take center stage, captured in scenes of life that are at times domestic, at times sacred and ritualistic. Among these are, for example, old family photos—taken in the intimacy of one’s home or during a trip—that are now made public and accessible. The database used contains countless self-portraits, but also photographs taken of relatives, in which small and large places of worship appear in the background. In a fast-paced and globalized time, it seems that the faithful feel an absolute need to capture and share an image of themselves that lends truth and authority to their existence, to their spiritualization. In Anyone’s Mother, there is also space for the representation of death, of celebrations, of the deceased. The tourist in Varanasi—often considered nonbelieving—is not permitted to observe too closely the bodies burning on the banks of the Ganges during the Hindu cremation ceremonies. And yet, the faces of those corpses, their details, can be viewed shortly afterward on a screen, by anyone, anywhere in the world. It thus seems natural to ask what truly makes human events sacred—from life to death: their unrepeatable occurrence in a specific time and place, or the moment and manner in which they are repeatedly shown and narrated. Why does virtuality, in the human imagination, manage at once to protect—thanks to physical distance—and to sanctify—thanks to narrative production (in all its forms)? And one cannot help but wonder who, in fact, is the author of these fragments of personal stories: the individual, compulsive users—or perhaps those who observe and select the images, creating from those many fragments a testimony, a collective History?